A wedding is the most joyful event in community life and, simultaneously, one of the most important ways of expressing its customs. It is a set of ritual actions with special symbolism and value for the newlywed couple who will not only perpetuate their family with their descendants but will also help increase the village population

In those days, apart from few exceptions, marriages took place by matchmaking, especially if the bride came from another village. Matchmaking was the usual process in finding husbands, and we find this out in the recorded responses of the village women to a related question.

A: – How did you get to Argyro Pigadi?

– By matchmaking. Around 40, 50 people came and took me…

B: – My husband saw me in Gouritsa, where we were after abandoning our village due to a rebel army invasion. And when we returned to the village, he sent his cousin to my father with a marriage offer.

C: – How did you get to marry your husband?

– My mother and father-in-law made the arrangement. We were plowing our fields together.

– Did they ask you if you wanted him?

– They did. And I said: “Since you say so, will I say no? To be ridiculed?

– Did you want him?

– I did, and he wanted me. Indeed, a lot.

– Did your fiancé visit you at your home?

– He came twice. And my mother told him: “You will not come again. Only as a bridegroom.”

Only in few cases a marriage came as a confirmation of a secret love affair since the strict-ruled society with high moral standards made it difficult for a love affair to become public.

D: I did not marry him by matchmaking. Just the two of us. He encouraged me by how he spoke to me because a man comes and speaks openly without seeming to be sly.

E: -I got my husband by matchmaking.

– Who was the matchmaker?

– A first cousin of my husband. He spoke to my father, and then he said it to me. Only two people in our village had an affair. Ilias Sotiropoulos and Loucia. One day they eloped. Elias took her, and they went to “curia.” They said: “If we don’t get married, we will kill ourselves. And finally, he took her as his bride… My husband made a wreath of vines, and the priest performed the ceremony.

The ritual events that preceded the wedding ceremony were related to the desire for the couple’s prosperity, longevity, and obtaining children. The wedding-related events began on Wednesday with a custom called “prozimia” (=leaven) at the groom’s house and on Thursday at the bride’s house. At first, they sifted the flour by which they would prepare the leaven to make the wedding bread.

Christoforos Karageorgos says,

“On Wednesday, they brought the wheat to the mill to be ground. I know this because my father was a miller. Whatever was in the basket was dropped and then they put the wheat for the leaven in it. As a fee, they gave the miller a “Kouloura,” a small round bread, a piece of cheese, and a bottle of wine. And they ate it together. The miller didn’t receive anything else as a payment.”

They put the flour in a large sieve which the children shook while singing: “It doesn’t pass, it doesn’t pass…” The adults then threw coins into the sieve, saying, “Sift, and it will pass.” At a certain point, of course, the sifting ended. They gave the coins to the children who took part in the sifting. Apart from the wedding bread, they also used the dough to make a cross on the house’s ceiling. They also sprinkled some flour on the bride’s head and wished her a long life, happiness, and many children.

On Thursday, the center of the joy was the bride’s house, where they prepared the bride’s dowry while singing and dancing. The dowry consisted of “flockates,” “velenzes”, blankets, carpets, and kilims. Then they made a pile out of them, a “giko,” and they placed a boy on top of it for good luck and to give birth to many boys. The dowry was completed with woven bags and various embroideries, all created by the bride’s and her mother’s skillful hands. Of course, the dowry included many purchased items: towels, pillows, sheets, tablecloths, etc.

On Friday, mules or women on their backs carried the dowry to the groom’s house.

On Saturday night, at the bride’s house, the “farewell table” was set where all her relatives participated. Like all feasts, this one also began with the song: “At this table, where we are…” followed by “On a Friday and a Saturday night, oh my mother, you send me away from your other children. And my father also tells me to leave…”

“My mother-in-law welcomed me.”

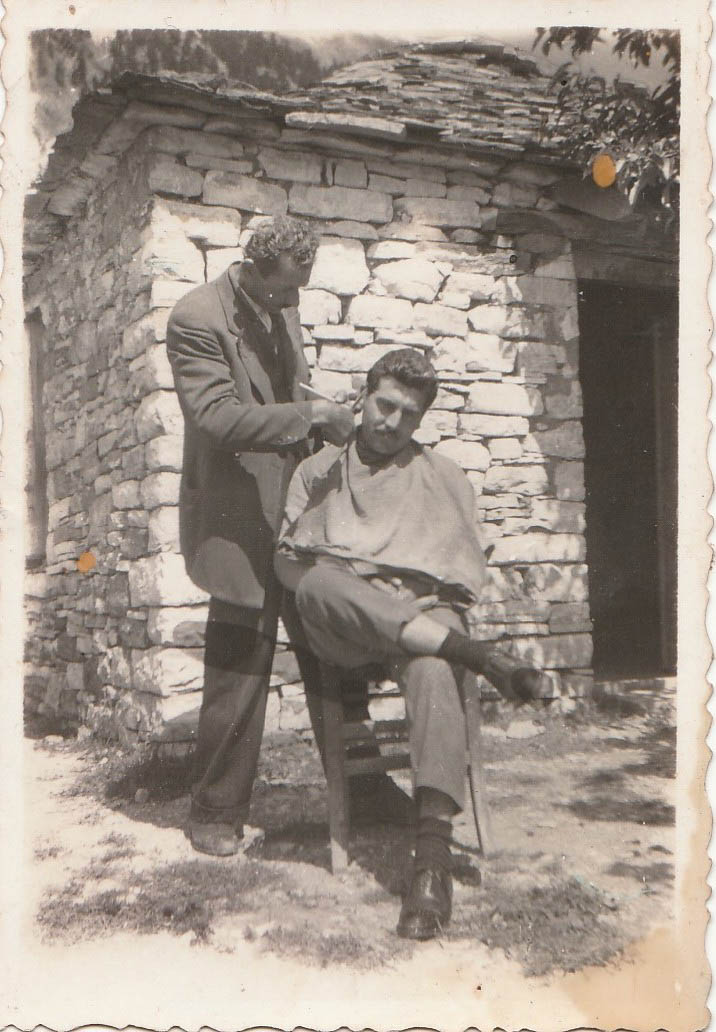

Sunday was the big day. First, they shaved the groom in a special ritual, and then the wedding group started from the groom’s house singing, “Let my eyes see how my love is doing….” They continued singing “Archontopoulo (=a Lord’s son) is going to crown…” and many other wedding songs.

The wedding procession, led by the groom, the best man, and a young man holding the wedding wreaths, headed to the bride’s house. His mother-in-law welcomed the bridegroom and offered him a glass of wine.

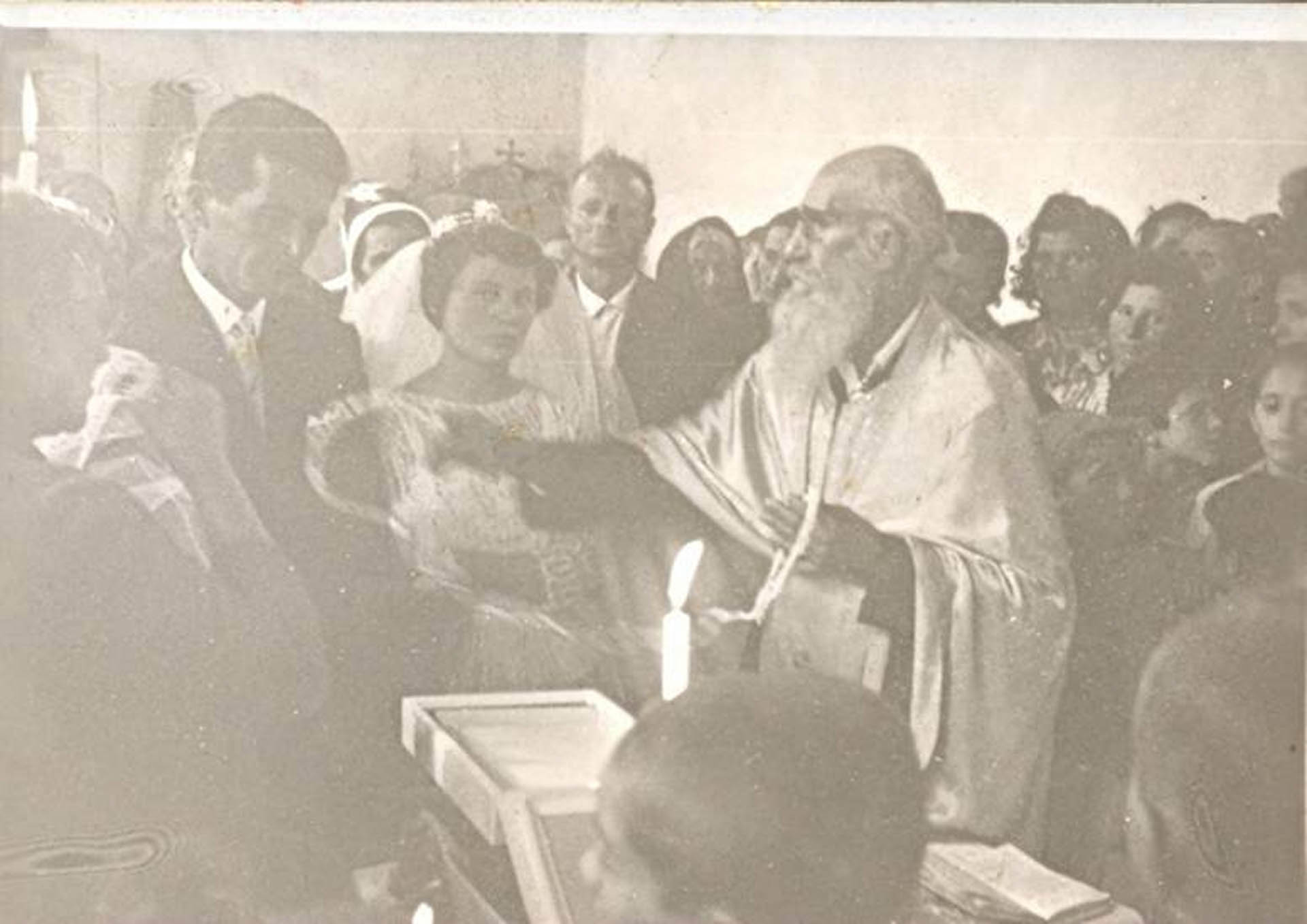

Then they took the bride with them, and they all went to the church for the ceremony.

After the ceremony in the church, the newlyweds and the guests went to the groom’s house, where the groom’s mother welcomed them at the front door and gave gifts to them. Then, according to the wedding etiquette, the bride threw apples, coins, and pomegranates to the guests, all symbols of fertility and well-being.

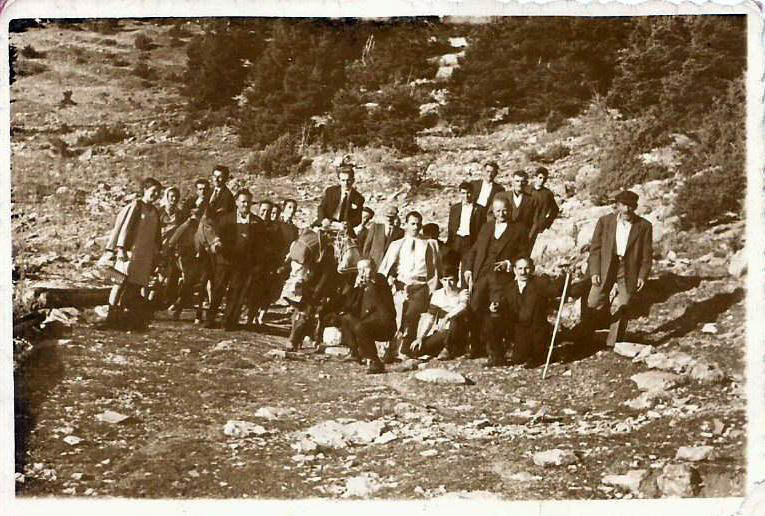

The feast lasted until Monday morning. To this feast, each guest family carried a basket containing the “provenda,” a decorated wedding loaf of bread, pies, and a variety of food.

The wedding was a significant event for the village, and all the villagers participated as guests. There had to be a bitter dispute between villagers so that one not be invited to the wedding. It was also an opportunity to restore relationships. The messenger, a relative of the bridegroom or the bride, went to the houses holding the “tsitsa,” a small, decorated, wooden wine container, and offered a glass of wine to the householder inviting him and his family to the “leaven” day, the “dowry” day and the wedding day. For the wedding day mainly, he made it clear if he invited them to the wedding group – the ones that would go to the bride’s village. The number of those attending the wedding ceremony and feast was roughly agreed upon because the house’s interior was narrow, and not everyone could be invited.

Rina Konstantinidis remembers and describes moments of her wedding:

“I still have the wedding dress. It was a crimson silk cloth. My mother bought it. I don’t know where from. And I went to Panetolio village to a seamstress, Christina, and she sewed it. The veil was regular, white. Mitrakis, the groom, wore a suit. He bought it when he was a soldier.

I came as a bride riding on a mule called “Roussa” of Giorgos Priovolos. He was my guide and advised me on what to do with the wedding bread and how to throw the apples. He made signals to me. We had a good wedding. My mother-in-law welcomed me. She wore a white scarf.

My mother-in-law and I went to the forest to fetch wood the next day. Dry and green together. Why? I don’t know.”