The geographical and environmental conditions determine the mountain population’s employment type, lifestyle patterns, and production methods. For centuries the primary sector has been the main source of living. Every mountain village household meets all its needs, relying on what they produce and what their home place provides.

The family first had to cover its essential need for bread, the essence and symbol of life. Therefore their main productive activity was agriculture.

Dimitra Sotiropoulou, a village resident, recalls:

We managed everything else. But if you opened the flour chest and there was nothing inside… We used to say, “Will we have bread by Christmas? Will we have it by Easter?”

The purpose of agriculture is to produce the necessary corn and wheat. Depending on the people who made it up, each family estimated the amount they needed from their experience. A large family needed 30 to 40 kados (1 kados = 38,5 kg) of corn and wheat to ensure the year’s bread. If there were more, they would give it to the animals.

However, the highlands were poor and stony, and the arable land was scarce and barren.

With wisdom, endless patience, and their hands as their unique tools, the mountain village’s people managed to transform the barren slopes into arable fields and terraces with drystone walls.

After cleaning the land, they used the stones they collected for the drystone walls.

They gathered the not used stones in piles, the “volios”.

At the same time, with the drystone walls and terraces, they protected the precious earth from the corrosive power of water. It was a constant and restless care for the inhabitants of a village built on a mountain slope. Each cultivator dug open ditches in their fields and directed the water to the nearest stream.

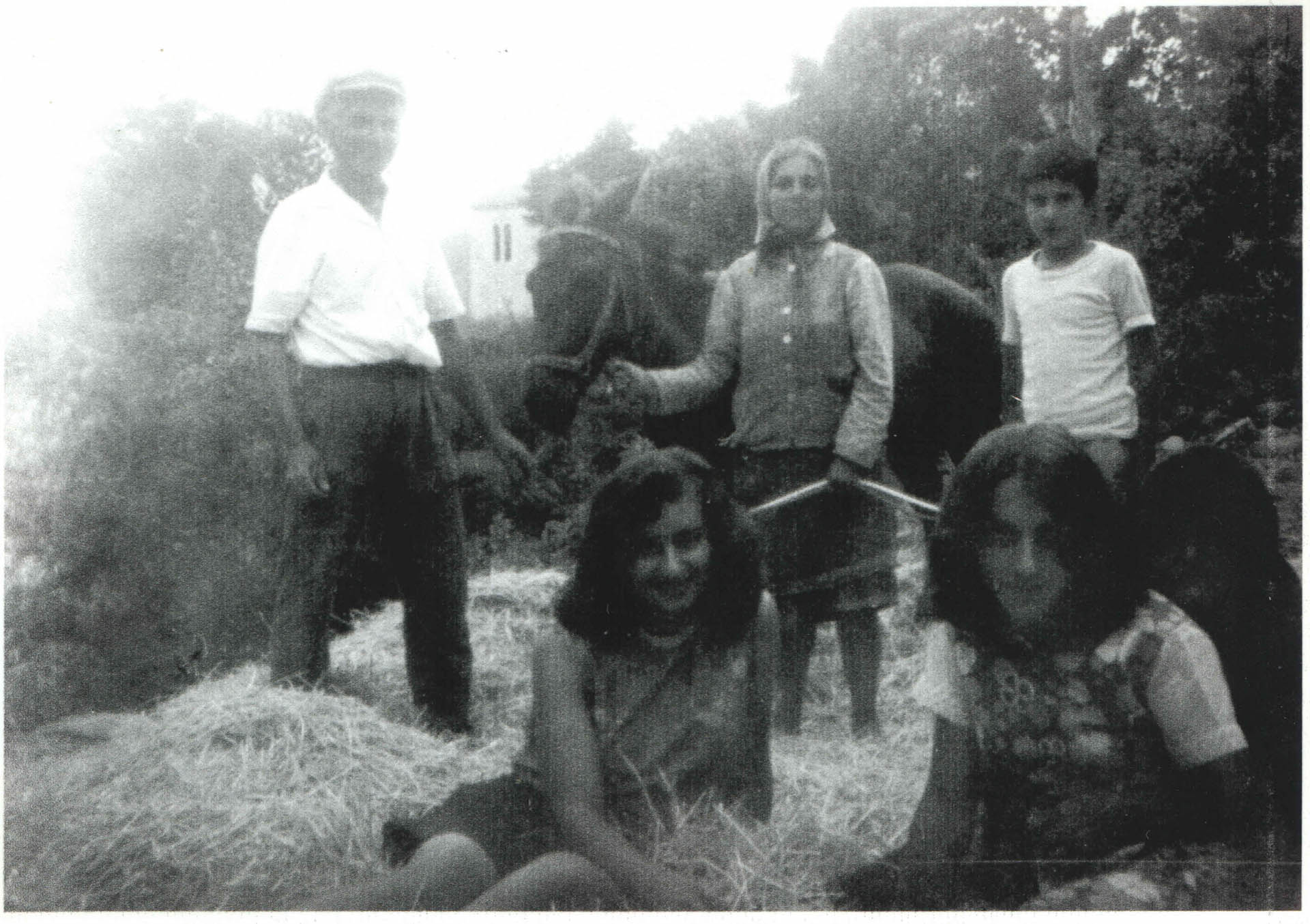

They used two oxen for the plowing, the wooden “Hesiodion” plow, and a yoke.

As a rule, each family had an ox, so they needed to find a partner to plow together. They joined forces to minimize the cost of keeping the animals.

Later, in the 1960s -70s, they replaced the pair of oxen with a hard mule and the wooden plow with an iron one.

Apart from working with the plow, everyone who could use a hoe helped in the fields.

They cultivate everything that can grow in the area and could use, especially corn and wheat, for bread, mainly corn. Because its cultivation is more efficient and less risky, it grows in the summer months and depends only on water, which is plentiful.

They also grow legumes: beans, lentils, chickpeas, and potatoes, as well as clover for fodder. They cultivate different species in the same field: maize and beans, which climb the corn, pumpkins, valuable human and animal food, cabbages, and more.

Not all fields are suitable for all crops. Long experience has taught them what they should cultivate and where, e.g., lentils in Vlasani and Kokkinalono and beans in Stournara.

Not all fields are suitable for all crops. Long experience has taught them what they should cultivate and where, e.g., lentils in Vlasani and Kokkinalon and beans in Stournara.

Argyro Pigadi beans were famous. Dimitris Loukopoulos writes:

“… we go downhill and reach a place, with many fields of corn and beans… If you eat Argyro Pigadi beans that boil in one water, you’ll want to tell it repeatedly throughout your life. It is the place that makes them so tasty and easy to boil.”

Kostas D. Maragiannis:

“Here they produce the best Aetolian beans, chestnuts, and cherries. “Whoever eats cherries from Gertovo will not grow old,” the sellers shouted at the Thermo market town in 1940.”

They alternate crops to maintain soil fertility. One year they cultivate wheat, and the next, corn. They grow both the irrigated and arid fields in the outer zone. Although their productivity is low, they are vital because they produce feed and keep foxes and badgers away from the most productive areas, avoiding damage.

They kept the best part of their production for seed. They changed it occasionally, taking it from other village producers or neighboring villages. They used varieties tested and adapted to the climate of their area.

Apple, cherry, walnut, and quince trees thrive in the village. However, they plant them at the edges of the fields so they do not shade them because “nothing grows in the shade.”

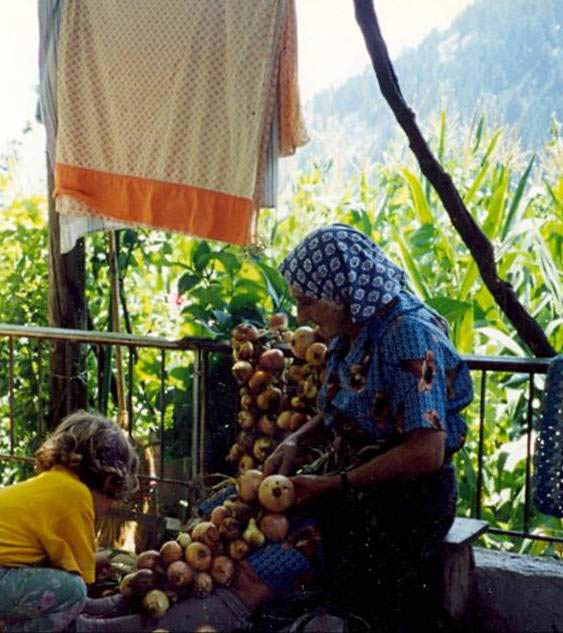

They grow tomatoes, cucumbers, beans, potatoes, and other vegetables and herbs in the garden. The aim is that every time the housewife goes to the garden to find something.

They prefer to plant them in “gournes,” small cavities in the ground. Their experience has taught them that it is more efficient. In this way, fertilization is easier because the plants keep more moisture, and when carving, they can gather soil more efficiently at the plant’s roots.

Generally, they meet the year’s needs by using whatever they produce. So, when the weather gets cold, and some tomatoes fail to ripen, they will become pickles for the winter.

The ears of wheat were piled on the threshing floors waiting their turn. A large threshing floor was that on the location “Stavros.” In the center of it, the “striouros,” a large stake usually of cedar, stood around which the tied animal, usually a mule, made circles.

The winnowing process followed so that the grains would come out clean.

An important moment after the corn harvest was the peeling time. Large groups gathered around the pile of corn early in the evening and peeled it from the outer leaves. Every afternoon and in a different house, this gathering had the character of a feast. They sang, told jokes, joshed with each other, remembered the old times, and told stories like the ones of Aristidis Talaganis, who invented elves, ghosts, and wild beasts, even mimicking their screams. Hence, people hid in their homes at night, and he, undisturbed, picked their grapes, figs, and vegetables.

At some point, they brought boiled chestnuts from the new crop. They soon ended with the corn pile, and then they danced and, tired but peaceful, went to sleep.

Giorgitsa Konstantinidis recalls:

“After we had harvested the corn in September, we put it in storage, in the yard, and in the evening, we used to say to the neighbors: “Tonight we’ll peel, come tonight to help us peel the leaves.” We gathered about twenty people, sometimes more. You could hear the jokes and the songs. When we finished peeling, we danced. We didn’t care if the night would pass or we had to get up early to work. It didn’t matter to us. Let us stay all night and let us dance around. Because we were young and enjoyed it no matter how tired we were.”

They let the corncobs dry in the sun for a few days, and then on the threshing floor, they beat them with a “drauli,” a flail, to get the corn kernels. They left them dry in the sun for a few days and finally put them in a large corn box. And from there to the mill to become flour and then bread.

Next to bread, the wine had a significant place at the family table. The Church blesses it, and people especially appreciate it because they gain strength and feel better when they drink it.

“…… When you would go to Argyro Pigadi fields to carve, water the fields, etc., if you had 1.5 to 2 kilos of wine and a mousountra (a kind of crispy pie) with you; if you had these things, you could work until midnight.”,

Dimitris Karagiorgos says.

Every household was quite interested in cultivating vines.

They cultivated vines at the bottom of each terrace or in vineyards. They cultivated varieties adapted to the region’s climate. The following grape varieties, “mavroudia” or “proimadia,” “melissakia,” “asproudes,” “filleria,” “politia,” and “kerkyraio” were very distinguished. «Aetonyhia» did not give wine, so they used to hang them from the ceiling inside the house and eat them in wintertime.

After they had harvested the grapes, they carried them in wooden boxes to the winepress. Sometimes the pressing was made in the field because moving the grapes on the back of an animal was difficult, as the paths were very narrow and steep.

They pressed the grapes with the “stoubos”- a big stick, in a wooden container, the “talaro,” and carried the must in leather bags, the “massines.”

The must ended in barrels, which they had thoroughly cleaned beforehand. They added resin and let it brew. Anyone who failed to do so could not be considered a competent householder.

The production of wine is also interwoven with tsipouro. After making must, they boiled the marc in a cauldron to distill the tsipouro. They sold some of the tsipouro production but enjoyed most of it alone.

“Bring us a tsipouro” was the householder’s usual command to his wife when a visitor arrived home for work or socializing.

Cultivation means water, and there was water in the village area, but the springs were not always close to the cultivated land. Carrying water from the springs to the fields was not an easy task. And, of course, prudent management was required because the water had never been abundant.

To be able to use the spring or stream water, first, they had to make a «desi,” that is to “catch” stream water, and then they diverted it into a ditch or a channel which could be several kilometers long, as the one that carries the water from the Gardikiotis spring to the village.

With the ditches, the running water is led directly into the fields or stored at night in reservoirs that open in the morning, and the water is released gradually.

The Community Council regulates all matters relating to irrigation. Two “neroforoi,” water carers, were appointed by the community council each year for the daily inspection of the irrigation water, and they were paid with corn depending on the amount of water that every receiver was entitled to.

Agreed…

Owning fields was vital for survival. The fields usually changed ownership when people left the village and sold their property or for other reasons.

Several purchase and sale contracts are among the documents presented at the Center. In some cases, they transferred a whole fortune that consisted of fields in many different locations, far from each other, a significant problem for the inhabitants of the mountain village.We also present a farm swap agreement as a solution for dealing with the problem of fragmented property.