In the mountain villages, all the inhabitants are traditionally occupied with animal farming and agriculture, producing grains, legumes, vegetables, and dairy products they need. But life creates needs requiring people with knowledge and skill to help the villagers address them. Housing, clothing, and tool repair are the most demanding.

Their living also requires goods their place does not provide: oil, salt, clothes, shoes, and tools. They had to buy these from the local cafes-groceries or in Thermo market town, so they needed money.

These necessities lead many people from Argyro Pigadi, in addition to being employed in the primary sector, to follow a profession useful to society. Sometimes this second occupation evolved into a primary or an exclusive one.

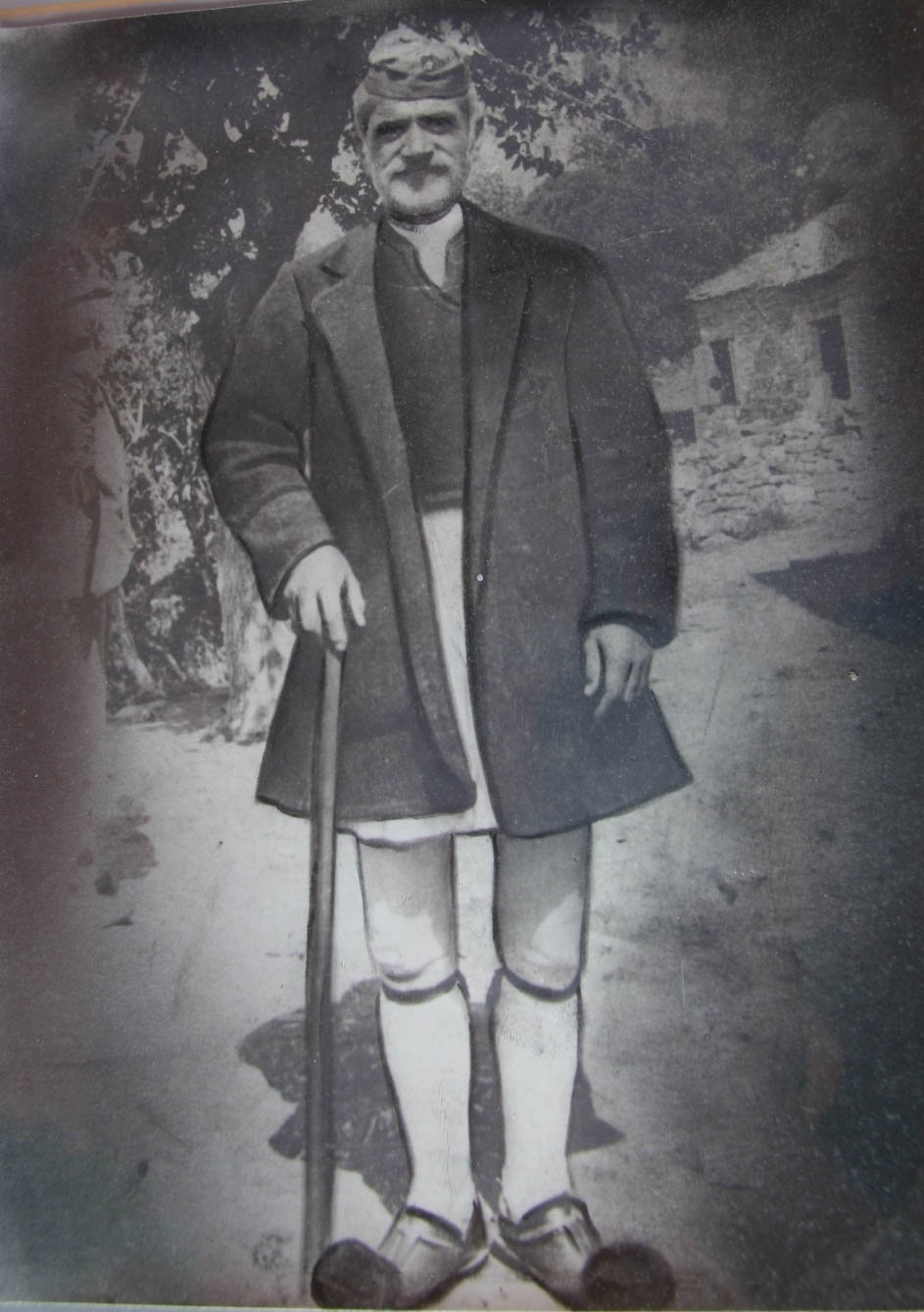

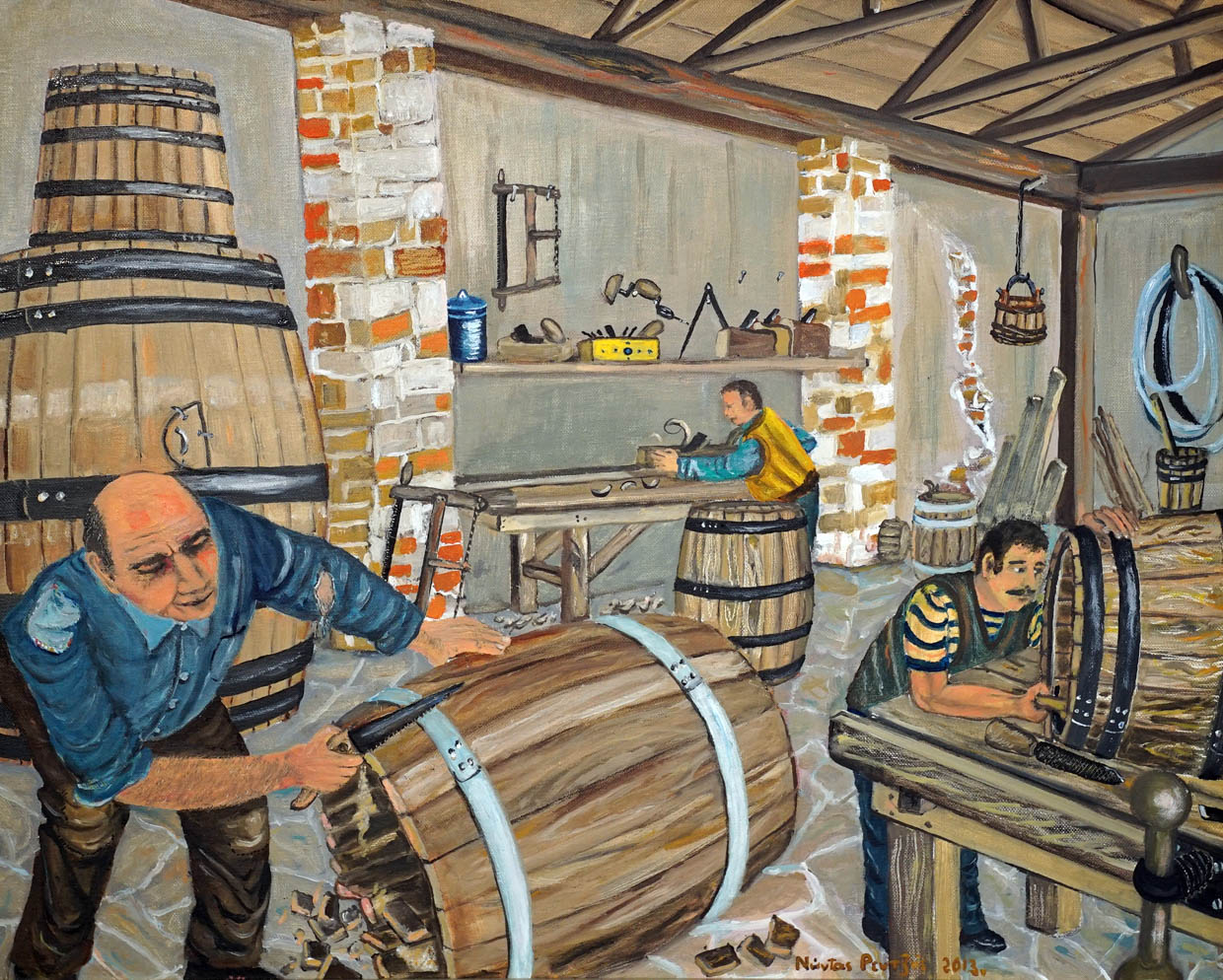

Many were craftsmen: builders, carpenters, coopers, and tailors, who worked in the village and neighboring villages and earned money.

Some testimonies:

Spyridoula Karageorgou:

“We never ran out of flour.” My father used to work as a day laborer. He cut boards….”

Rina Konstantinidis:

“My father never stayed at home… He was a day laborer as well. He cut boards with Vassilis Tsaparis and Lampros Karagiorgos…”

“We were not deprived of oil. My father was a tailor. He went to the villages and sewed. He sewed capes, trousers…”

recalls Dimitra Sotiropoulou.

Some worked during the harvest season picking olives or took care of obtaining fields with olive trees. Usually, they bought them with dowry money.

“Slowly. From where? Only 10,000 drachmas, and with that money, we got an olive tree field in Gouritsa,”

Dimitra Sotiropoulou answered when she was asked about her dowry.

Sometimes they made agreements to exchange products: beans with shoes, honey with oil. Yiannis Kostopoulos remembers:

“My father knew someone in Thermo, his name was Babatsikos Lambros, a shoemaker. My father had a pair of shoes made for each of us, one for my sister, one for my mother, and one for me, and the shoemaker’s pay, because my father had no money, was beans, ten okades of beans.”

But they mainly secured the necessary money by selling some of their products: beans, cheese, butter, leather, walnuts, and honey, as seen in the villagers’ testimonies.

Giorgitsa Konstantinidis:

“Beans. We picked a lot. The climate was favorable for them. We kept what we needed for the house and sold the rest. We also picked walnuts. As soon as we picked the walnuts, they would come and take them. We sold the walnuts. We also sold the beans, the surplus. We also raised lambs. We fed them to become big and sold them in the Thermo marketplace. But we would also sell a cow. We’d get another, but we’d gain something from that. And that’s how we earned money.”

Dimitris Karageorgos:

“We had three walnut trees. We used to get 120 to 150 okades of walnuts. My father used to go to Proussos and buy things”.

Ilias Tsolkas:

“My father and I used to take the cheese from here to Proussos and sell it to bring salt home.”

A mountain village that succeeds in living in conditions of self-sufficiency. Dimitris Loukopoulos writes characteristically in his book “Thermos and Apokouro,” in 1940:

“The village’s population is 198 souls, and they live on agriculture and animal farming. Here the sheep find their best grazing on the slopes of the Triantafyllia mountain. And so, Gertovos (Argyro Pigadi) people have their bread and legumes, they eat and sell, they produce plenty of wine, they also have plenty of dairy products, they eat and sell. The village produces a lot of chestnuts. A mountain village like this, whose people have everything they need, is rare. And this explains why the Aetolians lived up here in ancient times.”

The expenses note:

Expenses of 1900

| Cash for my home | Drach. 50.30 |

| I gave to John Antono. | Drach. 14.0 |

| I gave to Christos Panagi. | Drach. 26.80 |

| I gave to George Duros | Drach. 5 |

| To Ioannis Priovolos | Drach. 1 |

| I went shopping in Kefalovrison | Drach. 15 |

| I went shopping in Kefalovrison | Draxh. 10 |

| To the tax collector | Drach. 10 |

| 1 | |

| 132.50 | |

| For salt | Drach. 5 |

| To Kalatzis | Drach. 3 |

| For the heavy hammer | Drach. 1 |

For us, it is difficult to understand some expenses, such as “Cash for my home” 50.30 drachmas.

The other expenses are shopping in local shops (Antonopoulos, Panagiotopoulos), loan repayments or loans, shopping in Kefalovryso, and even paying the tax collector. Probably, it’s taxes.

And in addition: for salt, 5 drachmas, to kalatzis 3, for the heavy hammer 1.

Total expenses 141.50 drachmas

The note with the income:

Income of 1900

From cocoon 95.35 drachmas

From pig 14.25 drachmas

From maize 18.30 drachmas

From transports with the family’s mule or donkey, 18 drachmas.

These make a total of 145.90 drachmas.

And 9.18 drachmas are added from walnuts.

The family’s primary source of income is production.

The cocoon, which comes from feeding the silkworm that gives the wild silk, is the most important product. That’s why there are so many mulberry trees in the village. They also raised a pig for the house and one to sell. They sold corn and nuts. But the family also earned money from offering their services.

The conclusion is obvious. As a household and country, you cannot be self-sufficient if you do not have production. And you can have production if you take advantage of the possibilities your place gives you, whatever it is.

Note

Family of Paraskevi, widow of Papa-Charalambos Douros-Konstantinidis, with her four children aged 9 to 20 years.